Writer: Alaina Babb

Editor: Geetika Kosuri

The presence of internment camps full of American citizens—naturalized and natural-born—in the United States may seem impossible, as it would contradict constitutional protections to which citizens are entitled. Unfortunately, during World War II (WWII), roughly 110,000 Japanese Americans were relocated to internment camps.1 Milton Eisenhower, the head of the War Relocation Authority (WRA)—an agency created with the express purpose of forced relocation and internment of Japanese people and people of Japanese descent in the U.S.—described this as a mere “movement of…people of Japanese descent from their homes in an area bordering the Pacific coast into ten wartime communities constructed in remote areas between the Sierra Nevada Mountains and the Mississippi River.”2 The casual language surrounding these “relocation camps,” which were effectively concentration camps, in tandem with the perpetuation of the media referring to Japanese Americans in derogatory ways, such as describing them as America’s “fifth column” (defined as “a group of secret sympathizers or supporters of an enemy that engage in espionage or sabotage within defense lines or national borders”3) made possible the treatment of citizens as something less than such.4 American media perpetuated a false agenda about Japanese Americans, which led to the infamous Executive Order 9066, a blight on America’s history passed in 1942 by then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR).5 Thus, the internment of Japanese Americans was enabled by the media’s critical role in political control of public sentiment (i.e. propaganda), which exemplified the necessity of ethical media practices as well as media literacy and political awareness in preventing the occurrence of unjust legislative actions.

After the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor by the Empire of Japan, America’s general attitude towards Japan was amplified by fear and anger. Consequently, Americans came to accept that the U.S. would have to become involved in WWII.6 The following February, FDR signed into law Executive Order 9066, which gave the WRA permission “to take such other steps deemed advisable to enforce compliance with the restrictions applicable to each military area,” including superseding the Department of Justice “control of alien enemies.”7 It is interesting to note that the order itself does not explicitly refer to Japan itself or individuals of Japanese heritage; however, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, commander of the Western Defense Command, directly ordered the relocation and internment of people of Japanese ancestry, separating parts of the West Coast of the U.S. into Military Area One and Military Area Two, from which people of Japanese ancestry were excluded.8

The political discourse surrounding this unjust relocation elucidates how the American government influenced public perception of the internment camps and in turn justified this appalling violation of the U.S. Constitution. Various constitutional rights of the interned citizens were infringed upon, such as their right to due process as protected by the Fourth and Fifth Amendments,9 a suspension of habeas corpus since Japanese Americans were denied the right to challenge their detention, and many other examples as evidenced by life inside the camps, such as prohibition from assembly or free speech, rights protected by the First Amendment.10 As anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States began to rise, amplified by the attack on Pearl Harbor, there was limited hesitation about the internment of Japanese Americans. The unconstitutional act of relocating American citizens based on their race or heritage was overlooked due to the relatively poor media literacy of the American public and subsequent political unawareness as a result of unquestioningly accepting the propaganda that was sanctioned by the American media and government in tandem.

On March 24, 1942, the U.S. Army issued the first Civilian Exclusion Order concerning Japanese American relocation, “giving families one week to prepare for removal from their homes.”11 The swift escalation from December 1941 to March 1942 can only be fully understood in the observation of the media’s prejudiced portrayal of Japanese Americans before and during WWII. The Dies Report also played a key role in the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment in America at the time, inaugurating the “Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States,” which targeted citizens considered threats such as those deemed “Communist sympathizers” or people of German or Italian ancestry.12 This investigation was conducted between 1938 and 1942, notably beginning before the attack on Pearl Harbor, and did not result in the internment of any groups, ethnicities, ancestries, or affinities besides Japanese individuals.13 The closing statement of the amendment that addresses Japanese citizens reads: “The Japanese residents of California, Hawaii, the Philippine Islands, and the Panama Canal region [are] a menacing fifth column in the Territories of the United States.”14

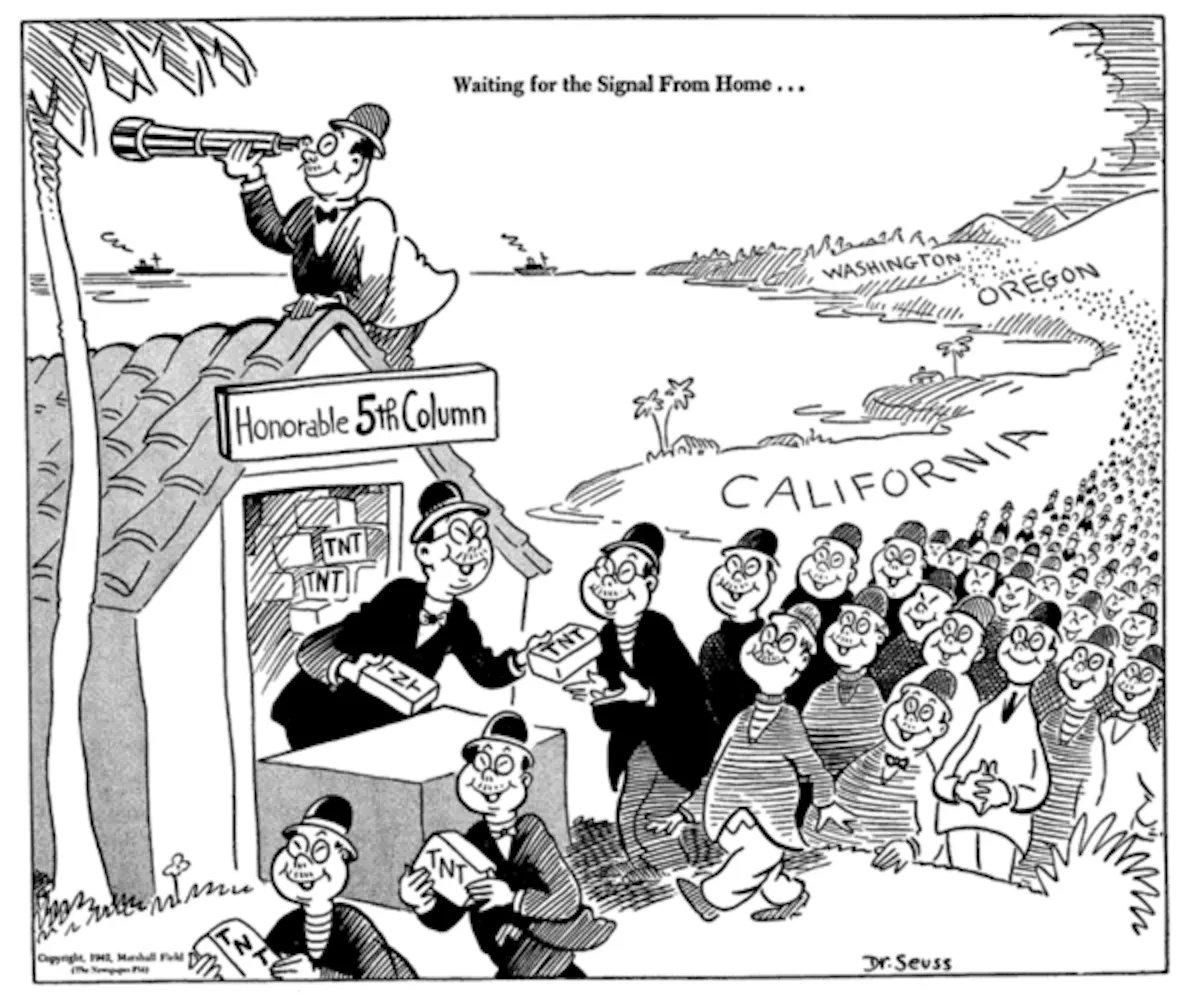

The use of the term “fifth column” was a recurring attribute prescribed to the Japanese people in American media, due in part to the fact that the Los Angeles Times offered Representative Martin Dies, the vanguard of this movement and namesake of the report, a platform as their “Japanese fifth column expert.”15 This is an example of a large media outlet espousing, without divergence from the opinion of Dies, a single narrative on Japanese Americans and the supposed threat they pose.16 Author Alice Yang Murray cites the portrayal of Japanese people as “spies and saboteurs” by popular news outlets as a reason for the existence of the Japanese Internment.17 This, coupled with highly offensive, racially divisive, and graphic propaganda, conditioned U.S. citizens to view Japanese individuals—regardless of their citizenship—as “un-American” and a threat to the American way of life.18

A prominent illustrator of these anti-Japanese posters was political cartoonist and children’s author Theodor Seuss Geisel, known by most as Dr. Seuss.19 A specific drawing of his references the popular “fifth column” label, illustrating dehumanizing depictions of Japanese Americans “waiting for the signal from home,” gathering explosives, implying and promoting the agenda that they are “spies and saboteurs” (see Appendix A).20

Japanese Internment during WWII demonstrates the troubling effect that the media has on public opinion, and the subsequent effect that public opinion has on legislative action. Thus, media literacy and political awareness are critical tools in preventing such gross violations of civil liberties in the future. The internment of Japanese Americans during WWII will continue to serve as a reminder of the dangers of unchecked government power as well as the vulnerability of marginalized communities and the ability for their portrayal to be manipulated by media narratives. By recognizing how doctored fear, prejudice, and sensationalized media rhetoric can fuel harmful policies, we are reminded of the responsibility to critically assess the information we consume and ensure that it aligns with our constitutional values. Ultimately, Japanese Internment during WWII serves as both a warning and a call to action to prevent history from repeating itself. It emphasizes the importance of vigilance and accountability in both the media and political spheres.

- Kimberley Roberts Parks, Revisiting Manzanar: A History of Japanese American Internment Camps as Presented in Selected Federal Government Documents 1941–2002, 30 J. Gov. Info. 573 (2004). ↩︎

- Id. at 578. ↩︎

- Merriam-Webster, Fifth Column (Feb. 2025), merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fifth%20column. ↩︎

- Lindsey Tanner, A Fanatical Fifth Column: The Media’s Argument for Japanese Internment, 11 Young Scholars in Writing 39, 39–46 (2014). ↩︎

- Libr. of Cong., Japanese-American Internment Camp Newspapers, 1942 to 1946, loc.gov/collections/japanese-american-internment-camp-newspapers/about-this-collection/#text2. ↩︎

- Parks, supra note 1. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Tanner, supra note 3. ↩︎

- U.S. Const. amend. IV & amend. V. ↩︎

- U.S. Const. amend. I. ↩︎

- Libr. of Cong., supra note 5. ↩︎

- Tanner, supra note 3. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Parks, supra note 1. ↩︎

- Tanner, supra note 3. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Parks, supra note 1. ↩︎

- Hampton Roads Naval Museum, Anti-Japanese Propaganda 1, history.navy.mil/content/dam/museums/

hrnm/Education/EducationWebsiteRebuild/AntiJapanesePropaganda/AntiJapanesePropagandaInfoSheet/Anti-Japanese%20Propaganda%20info.pdf. ↩︎ - Id. at 2. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

Featured image courtesy of: Dorothea Lange, Photograph of individuals waiting in line in front of a sign about people of Japanese ancestry, in Tim Chambers, Dorothea Lange and the Japanese-American Internment, Anchor Eds. (Dec. 2016), anchoreditions.com/blog/dorothea-langes-japanese-american-internment.

Leave a comment